While it is fun to bang away at buttons, we need to get to the heart of Max programming — and that involves numbers. Much of the number handling within the program is actually encapsulated into a few objects, with the most important being the number box.

The number box object

The number box object is another user-interface object. It allows us to input numbers, it can display numbers generated from other objects, it can temporarily store numbers and it can even help translate from one number system to another. Let’s begin with a simple patch.

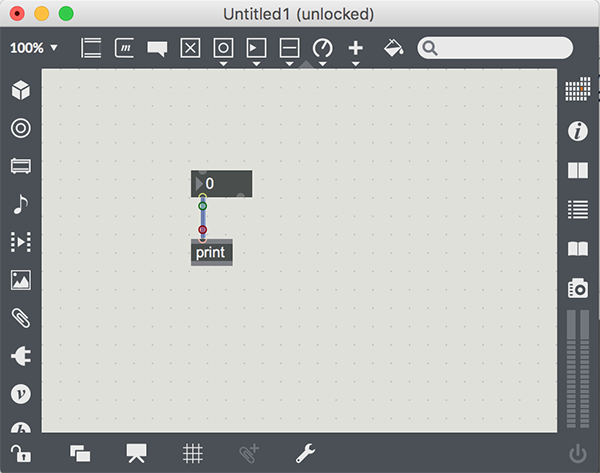

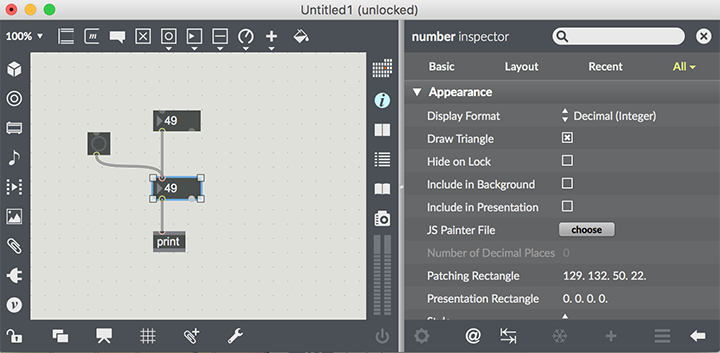

Start the Max program and create a new patcher window, then double-click to bring up the palette. These three steps should already be second nature, since they are the first things we do to create almost any patch. Select the grey square with a darker triangle in it (but not the one with the dot); this will add a number box to our patch. Add a print object, and connect the outlet of the number box to the print object. Your patch should look something like this:

Lock the patcher, click on the number box and type a whole number. The number box acts as a numeric entry field. If you hit enter, or click outside the number box, you will see that entry is complete, and the number box outputs the value (as seen in the Max Window).

There is another way to enter numbers. With the patcher window still locked, click on the number box and drag your mouse. You will see the number increment or decrement based on vertical motion. This scrolling mechanism is somewhat unique to the Max user interface, but it is a powerful and visual way to change values without using keystrokes. When you are scrolling the values, each new value will be sent out the outlet of the number box, and with a little scrolling you will quickly fill up the Max Window.

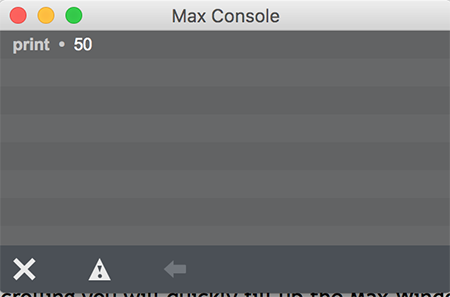

Let’s modify the patch by adding another number box above the previous one, and connecting its outlet to the inlet of the original number box. Your patch should look something like this:

Lock the patch and change the value of the top number box. You will see that, as soon as you are done entering numbers (or, if you are scrolling the top box, at each value change), the second number box’s value changes to match the first. What happened here? The value was sent from the outlet of the first number box, and received in the inlet of the second. When a number box receives a numeric message, it will change its value to match the input. It will also send the value out its outlet (thereby sending the number to the print object).

Also notice that if you change the value of the lower number box, it does not change the value of the upper box: messages flow from outlets to inlets, and never back “upstream”. This is important in understanding the “flow” of a Max patch.

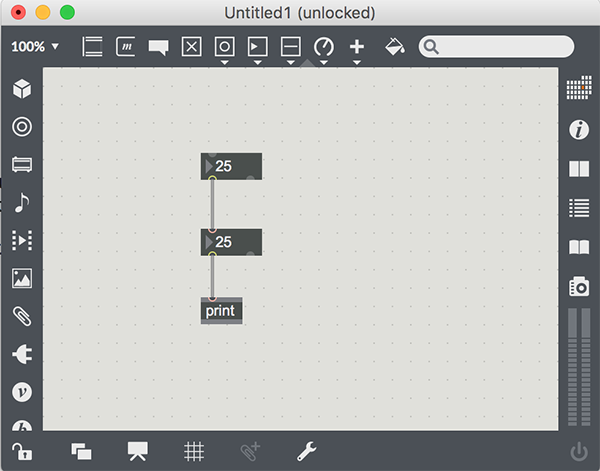

Let’s continue modifying the patch by adding a button object and connecting it to the original number box. Your patcher window should look something like this:

You can change the number box values, but if you stop and click on the button, you will see the current value sent to the Max Window. Remember that the button sends out a “bang” message, and that object that receives a bang will “do what it was designed to do”. The thing that the number box was designed to do was to send out a numeric value. Hence, when you bang a number box, you get its value sent from its output.

Let’s make one more change to this patch. Unlock the patch and click on the lower number box to select it. Then select Inspector from the Object menu. A new window will appear with a bunch of object attributes and their current values.

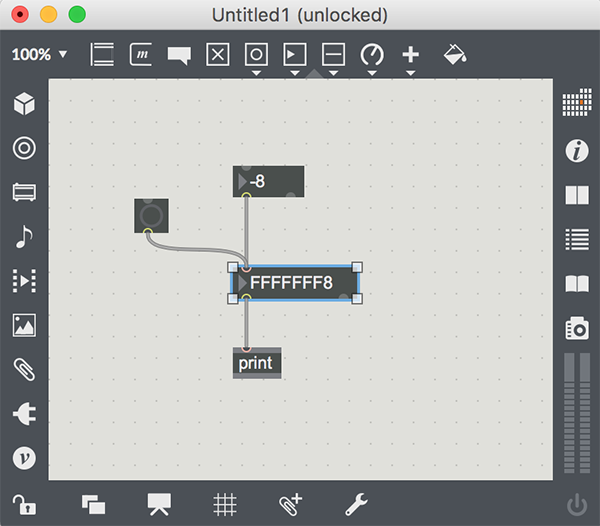

The top-most attribute should be called “Display Format”, and the current value will be decimal. This means that whatever the internal value is, the value displayed will be in decimal format. Click on the value and you will see a small menu appear. Select the value “Hex” from the list — you have now changed the display format to hexadecimal. Hexadecimal numbers are often used in programming, and you will see a lot of hex numbers when working with musical devices or microprocessors.

Close the inspector and lock the patch. Scroll the top number box, and see how the numbers in the lower box change. Hexadecimal digits go from 0 through 9, then A through F, giving us 16 digits for the base 16 number system. As you scroll the top box, scroll down to a negative number; you will notice that the lower number box fills with F’s at the beginning. You can make the number box larger by hovering your mouse over the right edge of the object until a little box appears. That box is a resizing control; clicking and dragging on this box will make the number box longer.

Let’s say that we don’t want the numbers to go into negative territory, since that makes for really large hex numbers. Select the top number box and open the inspector (with the Inspector option in the Object menu), scroll to the bottom of the attribute list and find the attribute labeled “Minimum Value”. It is currently set to ; double-click on that value and change it to “0”. This will restrict the number box values to non-negative numbers, preventing the display of too-large hex numbers.

Exercises:

-

Create a new patch with three number boxes across the top, all connected to one number box at the bottom. Change all of the values, and make sure you understand why things change the way they do.

-

Create a new patch that converts integer numbers into MIDI Note numbers. Hint: MIDI notes are limited to the range of 0-127, so you will want to prevent your input values from exceeding that range.

Friend Objects: The Math Operations

Max has a set of objects that are dedicated to math operations. These include the + (plus), - (minus), * (times), / (divide) and % (modulo) objects.

Each of these objects performs a single math function, and allows you to put in an argument to set a fixed operand. Here is an example of a simple patch that will add 10 to any number:

When you create one of these objects, you will notice that it includes a second inlet. This allows you to change the operand used in the calculation. Let’s patch up an example, using the * (times) operator.

Create a patch with two number boxes, each one connected to one of the inlets of a * object with an argument of 10. Connect the outlet of the * object to another number box. The results should look like this:

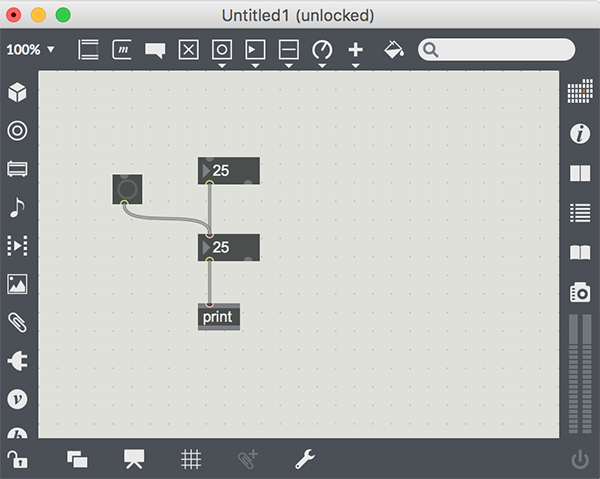

Lock the patch and change the top-left value to 20. You should see the output of the * object (as seen in the lower number box) change to 200. From this, we can see that numbers coming into the left inlet of the * object cause output to occur. Now change the value of the top-right object to 50. You will notice that nothing changes. What happened?

The right inlet of a math object is called a “cold inlet”. This means that it will accept information, but it won’t generate output. When is really happening is that the object is taking in the number you send it, storing it as the new operand, and is waiting for input to come into the left inlet so it can now multiply it by 50. Change the top-left number box to 10, and you will now see that the result (500) is using the new operand value for the multiplication.

Most people, at this point, wonder why the number inside the math object doesn’t change to match the newly input value (of 50, in this case). What you are seeing is the difference between a default value and a dynamic value. The argument that you enter into the math object is the default value; it will remain the same every time you open the patch, and will give us a starting value for calculations. When we change the operand value (the top-right value), this is a dynamic change, representing a transient value change rather than a permanent one.

Exercises

-

Create a new patch that takes one input number, and gives us the result of adding, subtracting, multiplying and dividing by 10. Have each result display in its own number box.

-

Modify the patch in exercise 1 to accept a second input that will change the operand in all of the calculations simultaneously. Hint: Dividing by zero is a bad idea in math, so you may want to limit the operand value to a positive number.

Friend Object: Slider

Sometimes, you just want a simple user interface element for setting or displaying a value without showing an actual number. In this case, the slider object is the answer. You will find the slider object in the object palette (which you get with a double-click on a blank part of the patcher window), near the bottom left of the object set.

When you create a slider, it is fairly simple: it has a border and a little bar. This bar is the control; if you lock your patch and click-drag on this bar, you will see that it slides up and down via mouse control. Unlock your patch and connect the outlet of the slider to a new number box. Now lock the patch and change the slider value — you will see that it outputs a number based on the bar’s position. By default, the slider object will produce (or show) numbers in the range from 0 to 127 (a parallel with the MIDI range of note values). You can change this to any range by selecting the object and changing the range value. Putting in a value of 500 will change the range to go from 0 to 499 (500 individual steps). You can also enter minimum values (which will change the starting point of your range) and a multiplier (which will perform an automatic multiplication of the output of your slider).

Exercise

Create a new patch with a slider connected to a multiply object with an operand of 10. Connect the output of the multiply object to a number box. Lock the patch and move the slider. Is there any way that this is different from using a number box as input?

Related Objects

All of the numbers we’ve worked with so far have been integer (whole) numbers. While these are useful, much of the interesting information is found between integers, in the world of floating point (fractional) numbers. Within Max, there is a separate stream of objects and procedures you use to work with floating point numbers.

The first, and most important, object is the floating point number box (or flonum). This is in the palette next to the regular number box — its only differentiation is that it has a decimal point in it (signifying that it is for floating point numbers). Create a new patch with one of these flonum objects in it, and connect it to a print object. Lock the patcher and change the values in the flonum object — you will find that it works much like the standard number box.

If you hook up a flonum to a math operation (such as * 10) and view the output (with another flonum), you will be surprised.

The result is still integer output, it only has a decimal point tacked to the end of it. The reason this happens is because, even though you are giving it a floating point number, the math object thinks it needs to work with integer value. In order to switch it to work with floating point numbers, we have to give it a “hint”. We do that by making the operand a floating point number. In this case, that would mean changing the “10” to a “10.0”.

Now we get the values we expect.

This is an important enough to put into bold print: If you want to end up with floating point data, every object in the calculation needs to be floating point!

Finally, to get the slider to produce or show floating point numbers, we need to change one of its attributes. Create a new slider, select it and open its inspector. Find the attribute called “Float Output” and turn it on (by clicking on the check mark). Now connect the slider’s output to a flonum and move it around. You will see that it outputs fractional values rather than just integers.

Exercise

One of the classic Max exercises is to convert a Fahrenheit temperature into its Celsius equivalent. This is done by taking an input value, subtracting 32.0, multiplying by 5.0 then dividing the result by 9.0. Using a slider on the input and a flonum to show the results, try to create an F-to-C conversion patch.

More on Trigger

In the last lesson, we saw that the trigger object could produce output in a specified firing order. Trigger also has three more properties: it can pass data through (in the defined order), convert data to a specific type, and generate predefined data entered in as an argument.

Create the following patch:

We have two different trigger objects: one with an integer number box for input, the other with a floating point input. In each case, the value is fed to a trigger (“t”) object with the arguments “b i f”. These arguments stand for “bang”, “integer” and “float”, and determine the output of the related outlet. If you enter a number into either of the number boxes, you will see that the results sent to the Max Window are of the appropriate type. If a number has to be converted, the object will do so automatically.

We can also force a specific value out of one of trigger’s outlets. Build this patch:

Now, a trigger object with the arguments “i f 20” will output an integer and a floating point number, but the first value that is produced will always be the integer number “20”, since this is a static value provided as an argument. Also, notice that if you click on the button to send a bang into the trigger object, the default values of 0.000000 and 0 (plus the default “20”) will be sent out the trigger object’s outlets, since the bang message has no intrinsic numeric value.

Theory

Earlier, we saw that the math objects only create output when numbers come into their left inlet. Numbers coming into the right inlet are stored, but don’t generate any output. There is a name for this difference: the right inlet is called a “cold” inlet, and the left inlet is called a “hot” inlet. Remember: Hot inlets generate output, cold inlets do not.

You can determine if an inlet is hot by hovering your mouse over the inlet; cold inlets will have a blue circle around them, while a red circle indicates a hot inlet. This works for every object, not just math objects. Whenever you are using a new object, you can always figure out the generation of output by checking the hot or cold status of the inlets.

What do you do if you want to generate output when all you are changing is cold inlet data? This is a great place to use the trigger option with our new argument options. By using a “t b i” trigger, we can send the value to the right (cold) inlet of the + object, then send a bang message to the hot inlet — forcing a recalculation of the addition and output of the new value.

So how do we patch this? Here’s an example:

You can change the top-left value and will get a standard calculation. Now, however, when you change the top-right value, it will also generation a new calculation with the new operand. Why is the argument set “b i” instead of “i b”? It’s all part of the right-to-left scheme of Max: by putting the value to the right of the bang, it makes certain that the number gets to the object before the bang message forces the calculation. This is a pattern that we will see in many other instances.